The History of Les Halles

Les Halles Centrales de Paris: A Monumental Evolution of Urban Architecture and Commerce

Les Halles Centrales de Paris stands as a cornerstone of the city's commercial, architectural, and cultural heritage. From its inception in the medieval era to its modern transformation, Les Halles exemplifies the dynamic interplay between tradition and innovation, reflecting the evolving needs and aspirations of Parisian society.

Medieval Origins and Early Development

The origins of Les Halles date back to the reign of Philippe-Auguste (Philip II of France) in the 12th century. Initially, the area was a vast marshland known as the Champeaux, which was drained and transformed into meadows to support Paris's growing population.

Recognizing the necessity for a centralized marketplace, Philippe-Auguste established Les Halles as the primary hub for the exchange of essential goods, particularly grains, vital for sustaining the city's residents. Originally, the site served dual purposes: a market for the living and a cemetery for the dead. This juxtaposition, although seemingly macabre by today's standards, was common in medieval urban planning.

Establishment of Les Halles

- 1137: Louis VI purchased the land known as des Champeaux or "Petits-Champs" to establish a market.

- 1180-1183: Philip Augustus fortified the area with walls featuring gates closed at night and built sheds to protect goods from the weather.

14th Century Growth

By the 14th century, Les Halles had expanded significantly, with merchants and artisans from various communities each having their own hall. Streets were formed by shops of the same trade, including:

- Tixanderie (Furriers)

- Ferronnerie (Blacksmiths)

- Chanvrerie (Hatters)

- Haumerie (Hairdressers)

- Cordonnerie (Shoemakers)

- Lingerie (Linens)

- Triperie (Leather Goods)

- Poterie (Pottery)

- Friperie (Second-hand Clothes)

- Potiers-d'Étain (Tin Potters)

- Fourreurs (Food Vendors)

Types of Halles

Covered Halles (7)

- Halle aux Draps (Drapes Hall)

- Halles aux Toiles (Canvas Hall)

- Halles aux Cuirs (Leather Hall)

- Halle à la Saline or Fief d'Alby

- Halle à la Marée Fraîche (Fresh Tide Hall)

- Parquet de la Marée (Tide Parquet)

- Halle aux Vins (Wine Hall)

Open Halles (11)

- Halle aux Blés et aux Grains (Grain and Wheat Hall)

- Halle à la Farine (Flour Hall)

- Halle aux Beurres (Butter Hall)

- Halle à la Chandelle (Candle Hall)

- Halle aux Chanvres, Filasses et Cordes à Puits (Hemp, Filasses, and Rope Wells Hall)

- Halle aux Pots de grès, à la Boissellerie (Pottery Hall, Boissellerie)

- Halle à la Chair de Porc Frais et Salé (Fresh and Salted Pork Meat Hall)

- Halle au Poisson d'eau douce (Freshwater Fish Hall)

- Halle au Pilori (Pillory Hall)

- Halle aux Poirées (Bouquets, Herbs, Fruits Hall)

- Rue aux Fers (Reserved for Gardeners)

Architectural Enhancements Under Henri II

In 1550, during the reign of Henri II, the architectural landscape of Les Halles underwent significant transformation. Pierre Lescot, a renowned architect of the time, was commissioned to elevate the aesthetic and functional aspects of Les Halles.

Lescot constructed a loggia adorned with sculptures by Jean Goujon, introducing a blend of architectural grace and structural solidity. This loggia, consisting of three arcades, became a focal point of the market, enhancing its grandeur and utility. These enhancements not only beautified the market but also solidified its role as a central economic and social space in Paris. The three arcades, later integrated into the Fontaine Monumentale, remain a testament to Lescot's architectural prowess and Goujon's artistic finesse.

Renovation of Les Halles

1543-1572: François I began the reconstruction of Les Halles, which was completed by Henry II. This renovation, known as the Renovation of Les Halles, established Les Halles as a central marketplace with designated areas for goods that remained largely unchanged until the mid-19th century.

18th and 19th Century Expansions

The 18th century witnessed further expansions of Les Halles to accommodate Paris's burgeoning commercial activities. Notably, in 1763, the construction of the Circular Hall began under the direction of Le Camus de Mézières, culminating in its completion in 1772. This circular hall, characterized by its robust stone facade and intricate window designs, exemplified the architectural style of the period, emphasizing both functionality and aesthetic appeal.

In 1772 the Halle aux Blés (Wheat Market) replaced the Hôtel de Soissons, becoming a central hub for grain trade.

New Specialized Markets

- Poultry and Game Market (1812)

- Cheese Market (1836)

- Onion Market (1822)

The Innocents Cemetery and Market

Adjacent to Les Halles, the Innocents Cemetery was a significant landmark until its demolition in 1786. By 1789, the area became the Innocents Market, focusing on herbs and vegetables, before its closure in 1858.

19th Century: Centralization and Renovation

With Paris's rapid urbanization, Les Halles underwent comprehensive redevelopment:

- Centralized Markets: Markets were consolidated into pavilions, such as the Butter Market (1858) and the Vegetable Market (1857).

- New Structures: Significant investments were made to replace aging wooden structures with modern facilities, like the Halles Centrales, which grouped various markets into dedicated pavilions.

Major Developments and Final Reorganizations

- Meat and Poultry Markets: Relocated multiple times before settling in dedicated pavilions in the 1860s, including Pavilion No. 3 for wholesale meats and Pavilion No. 4 for poultry.

- Fish Market: Initially located in the Cour des Miracles, it moved to the Carreau du Pilori in 1822 and finally to Pavilion No. 9 in 1857.

- Halle aux Huîtres (Oyster Market): Established in 1845 on Rue Montorgueil, it was later moved to Pavilion No. 12 in 1866.

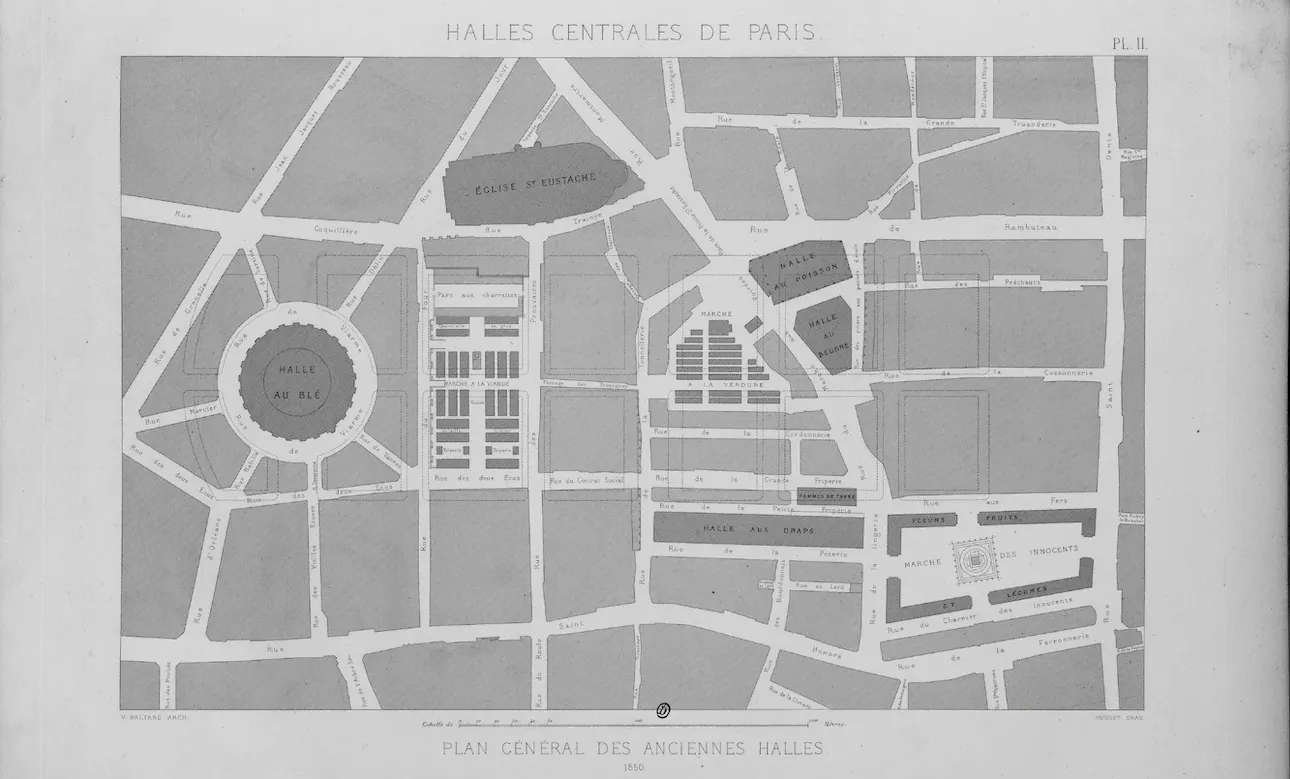

By the mid-19th century, the existing structures had become overcrowded and architecturally disjointed, prompting the need for a comprehensive redesign. The chaotic amalgamation of various architectural styles and structures, often described as a "fouillis de constructions hybrides," underscored the pressing necessity for modernization.

Victor Baltard and Félix Callet: Architects of Modern Les Halles

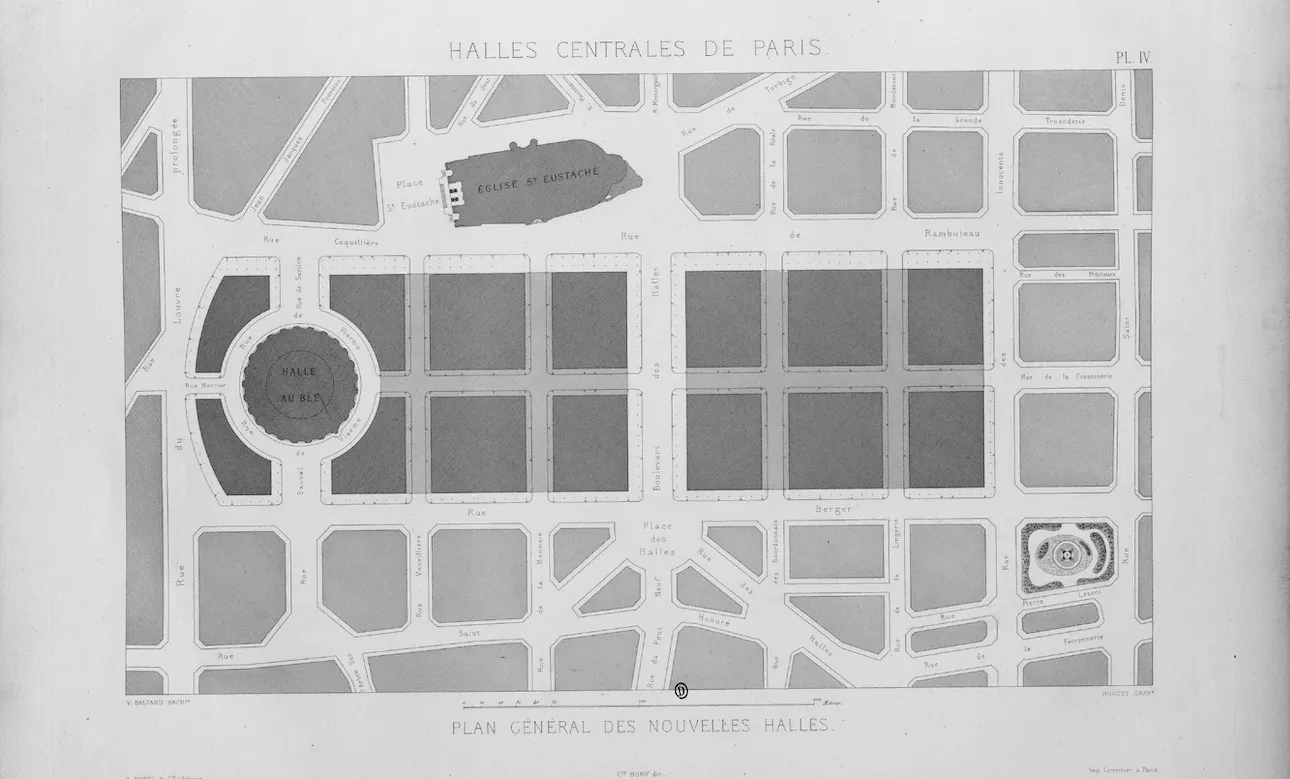

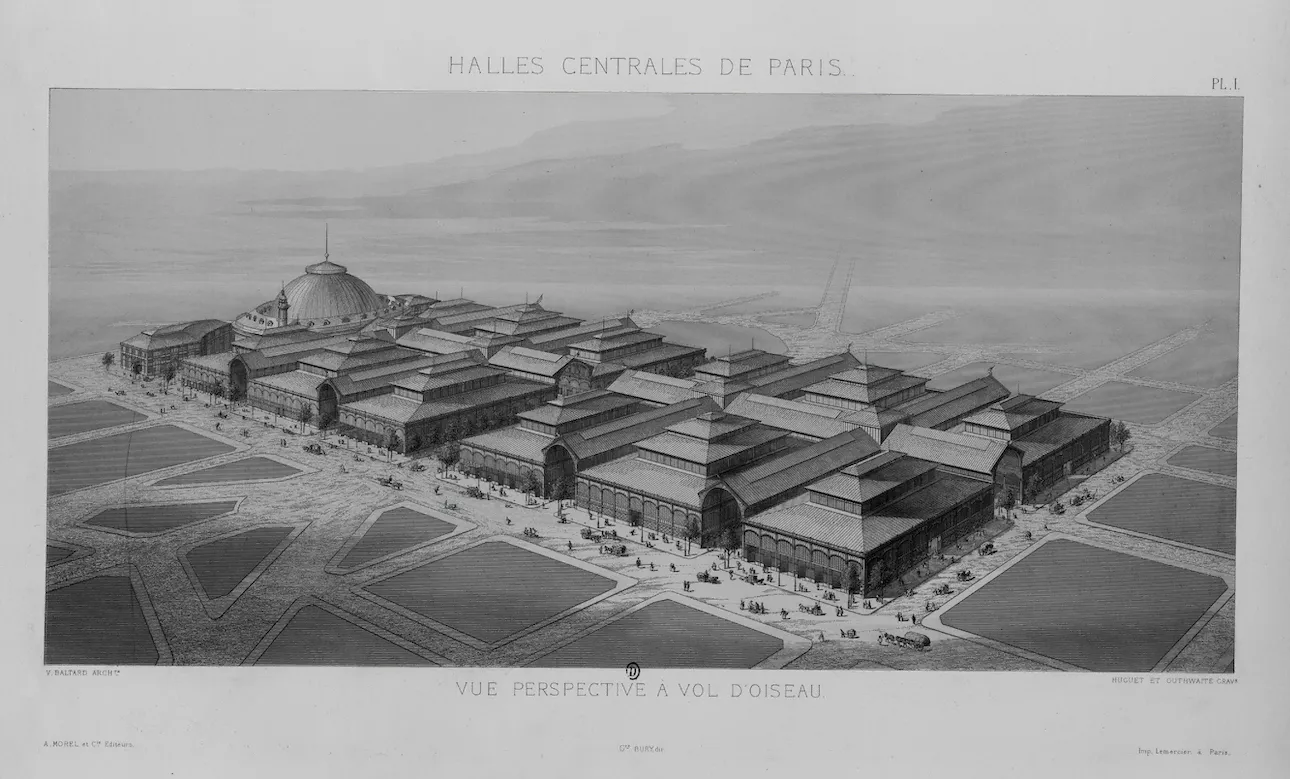

In 1842, the question of reconstructing Les Halles resurfaced, leading to the involvement of Victor Baltard and Félix Callet, two visionary architects who would redefine the marketplace's architectural identity. Commissioned by the municipal administration in 1845, Baltard and Callet embarked on a transformative journey to modernize Les Halles, embracing industrial materials and innovative design principles.

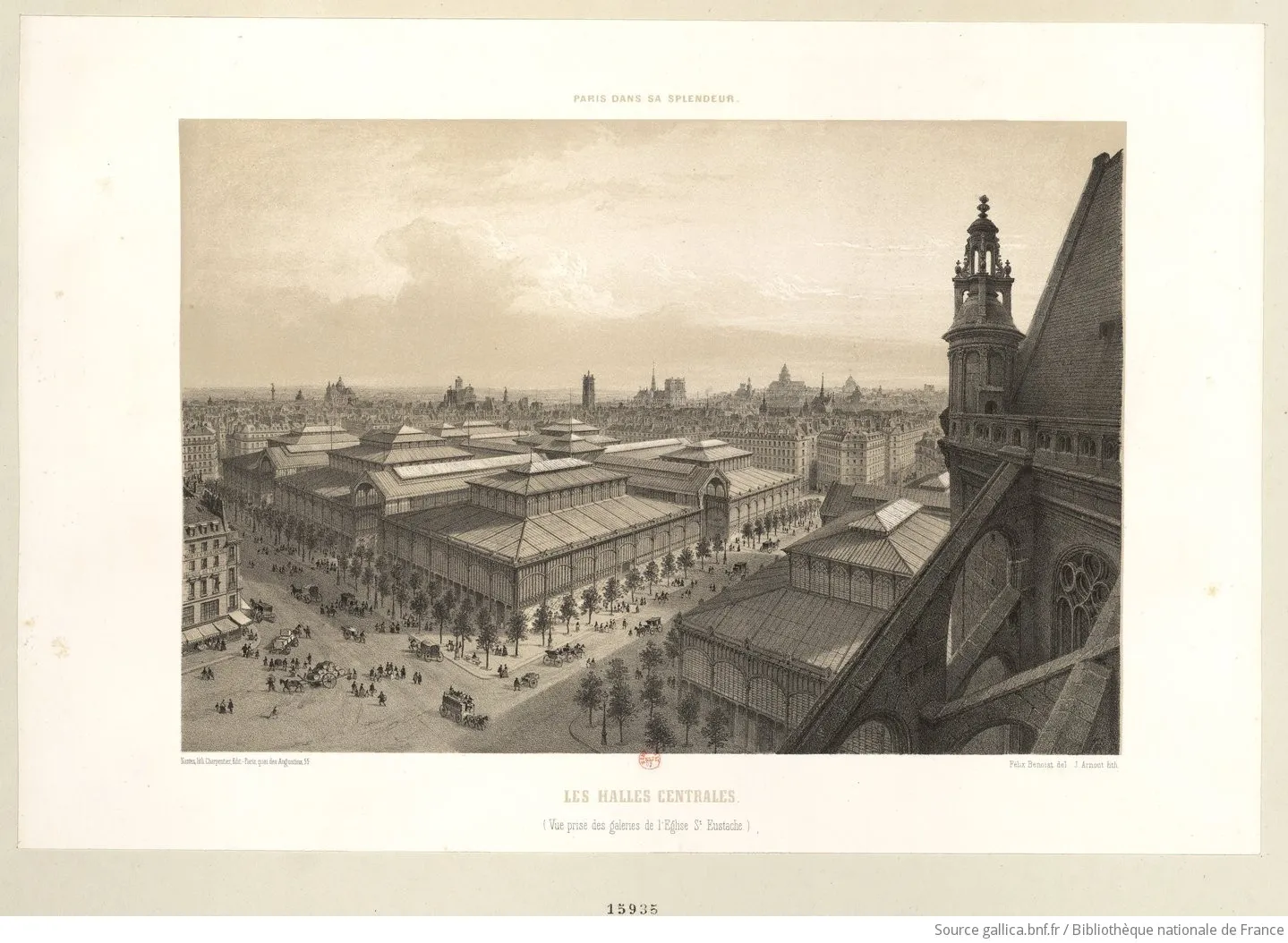

Their design philosophy was rooted in the principles of industrial architecture, utilizing iron and glass to create expansive, airy spaces that were both functional and aesthetically pleasing. This marked a significant departure from traditional stone and brick constructions, allowing for larger open spaces, enhanced ventilation, and increased natural lighting—critical factors for a market handling perishable goods.

Key Architectural Features

- Iron Frameworks: Provided structural support, enabling the creation of vast, unobstructed interior spaces.

- Glass Roofing: Facilitated ample natural light, reducing the need for artificial illumination during daytime operations.

- Symmetrical Pavilion Layout: Organized the market into specialized pavilions, each dedicated to different types of produce, ensuring efficient circulation and functionality.

- Ventilation Systems: Advanced designs ensured optimal airflow, maintaining the freshness of goods and a comfortable environment for both vendors and shoppers.

Émile Zola immortalized Les Halles in The Belly of Paris (1873), portraying it as a vibrant hub of commerce and prosperity.

Technological Innovations and Sustainability

Baltard and Callet's design integrated several technological advancements that were ahead of their time:

- Ventilation and Climate Control: The innovative ventilation systems ensured constant airflow, reducing the risk of spoilage and maintaining a pleasant shopping environment.

- Gas Lighting: Enhanced illumination during evening hours, improving visibility and safety within the market.

- Water Management Systems: Efficient canal and sewer systems supported the market's operational needs, demonstrating a keen understanding of urban infrastructure integration.

- Modular Design: The use of standardized modules allowed for flexibility and scalability, enabling the market to expand and adapt to growing demands.

Architectural Legacy and Innovation

The architectural innovations introduced at Les Halles by Baltard and Callet inspired other architects to explore similar techniques, particularly the use of iron and glass in large public structures.

Transition to a Modern Marketplace

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Les Halles had firmly established itself as a modern marketplace. The seamless integration of industrial materials with traditional architectural elements created a harmonious blend that set a precedent for future urban constructions in Paris. However, as Paris continued to grow and evolve, the needs and expectations of its populace necessitated further adaptations, leading to the eventual redevelopment of Les Halles into a contemporary shopping and cultural complex in the late 20th century.

Centralized Renovation Under General de Gaulle

General de Gaulle, despite being deeply involved in the Algerian issue, turned his attention to the renovation of Paris in 1959. With the assistance of André Malraux, he focused on the Les Halles district, initiating the transfer of its activities to Rungis.

- March 14, 1960: President General de Gaulle decided to relocate Les Halles—the central wholesale market for fresh food in the heart of Paris—to Rungis and La Villette by November 1, 1968. The actual transfer occurred between late February and early March 1969, chosen for its ample land and proximity to the newly built Orly Airport.

This relocation freed up over 35 hectares in Les Halles, setting the stage for a major urban redevelopment project aimed at transforming the area into a symbol of political and artistic significance.

Redevelopment Vision and Challenges

The redevelopment of Les Halles was envisioned as a flagship project that would not only solve logistical issues related to food distribution and traffic but also serve as a beacon of political and artistic innovation. The project aimed to create a space that reflected France’s modernization while maintaining cultural heritage. Six diverse architectural proposals were developed, each offering unique visions for the district's future.

The Permanent Group, consisting of architects and urban planners, developed preliminary projects influenced by consultations with six architects. These proposals ranged from conservative conservation efforts to bold, futuristic designs. Jean Faugeron’s innovative project gained favor due to its artistic originality, aligning with de Gaulle and Malraux’s vision for a modern yet culturally significant Les Halles.

Despite differing opinions within the government, Faugeron’s design was ultimately preferred, emphasizing the integration of cultural and administrative functions within the renovated district.

The upheaval of May 1968, marked by widespread protests and social unrest, significantly disrupted the Les Halles project. Financial constraints and shifting political priorities led to the postponement and eventual abandonment of the original redevelopment plans. The crisis underscored the challenges of balancing modernization with social stability, resulting in the project's incomplete realization during de Gaulle’s tenure.

1969: "The Hole of Les Halles"

The old pavilions were deemed unsanitary and demolished, leaving a massive crater, nicknamed "Le Trou des Halles," in the heart of Paris. The wholesale market operations were relocated to Rungis in an ambitious move involving 20,000 workers, 1,000 businesses, and 5,000 tons of goods.

Italian filmmaker Marco Ferreri used the site for his 1974 film Touche pas à la femme blanche!, transforming it into a surreal backdrop for a reimagined Battle of Little Big Horn.

Revitalization of the Beaubourg Plateau and Les Halles District

With the completion of the Pompidou National Center in 1974, the Beaubourg Plateau has become a vibrant area, closely linked with the Les Halles district in Paris. Since its opening, the Pompidou Center has gained worldwide acclaim and has rapidly emerging as a major tourist attraction.

1979: The Forum des Halles

The crater was replaced with a modern underground shopping mall designed by Claude Vasconi and Georges Pencreac'h. The RER Châtelet-Les Halles station was also inaugurated.

- 1979: The Forum shopping center was inaugurated, offering 50,000 square meters of cinemas, fashion boutiques, restaurants, and major retail stores for photography and household appliances.

Located entirely underground with skylights, the Forum includes extensive parking facilities, underground vehicle circulation, and connections to the RER and metro systems. The introduction of the regional express network and metro station transformed the neighborhood into a central transit hub for all of Paris.

Subterranean Design

The Forum des Halles extends 22 meters underground, comprising 8 levels (5 of which are subterranean). Features include:

- 7 main entrances, with Porte Lescot being the most frequented

- Labyrinthine layout, reinforcing the space as one of transit rather than destination

- Limited visibility depth and a high density of metal walls and glass surfaces restricting natural light and visual openness

Post-8 PM, the area empties significantly, with only transit-related activities remaining

Châtelet-Les Halles: A Modern Transport Marvel

December 9, 1977: Châtelet-Les Halles, Europe's largest underground station, opened to the public as part of the revolutionary Réseau Express Régional (RER).

Located at the heart of Paris, Châtelet-Les Halles became the crown jewel of the RER network, linking three lines (A, B, and D) with a massive commercial hub, the Forum des Halles. This station exemplified modern engineering with:

- Seven tracks to manage high traffic volumes

- Multimodal connections with metro lines and regional trains

- Advanced construction techniques to stabilize surrounding buildings, creating an architectural and engineering feat

Initially served by RER A and B, it became a key component of Paris's effort to modernize and connect the city to its suburbs. In 1987, RER D also began operations at the station, making Châtelet-Les Halles the only station managed by RATP to serve this line.

The Broader Impact of RER

By the late 1970s, the RER redefined urban transit with innovative features:

- High-capacity trains capable of 100 km/h speeds

- Monumental stations designed for efficiency and aesthetics

- Seamless integration of RATP and SNCF networks, enabling suburban trains to traverse Paris

- Magnetic ticketing system and the popular Carte Orange subscription further simplified travel, fostering public adoption of this groundbreaking system

Maintaining Residential Presence

To preserve the neighborhood’s identity, the master plan allocates 192,000 square meters for the entire scheme, including 51,000 square meters dedicated to housing in Les Halles. The aim being to find a balance between the dominant shopping center and residential needs, with 27,000 square meters of housing specifically programmed to reintegrate residents into Les Halles and support personal and community development.

- 1985: The Place Carrée, designed by Paul Chemetov, was added, featuring distinctive arches and a grid-patterned floor.

Les Halles became a symbolic space for various urban subcultures, notably the hip-hop movement, contributing to its mythic status among certain groups, acting as a stage for cultural expression, despite the overarching control and regulation imposed by its architectural and managerial frameworks.

Master Plan: Linking Pompidou, Forum, and La Bourse

The alignment of the Pompidou Center, the Forum, and La Bourse forms a central axis that underpins a comprehensive three-phase master plan. This plan aimed to integrate the Les Halles district with the Beaubourg Plateau, harmonizing their activities and functions.

Vision of a Cosmopolitan Pedestrian Center

The master plan envisions a unified cosmopolitan pedestrian center, comparable to other major Parisian landmarks. Unlike traditional Haussmannian spaces, this new center is designed as a dynamic convergence of activities, embodying 21st-century ideals of energy, community, and self-sufficiency.

Modern Transformation: From Market to Cultural Landmark

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, recognizing the need to modernize and repurpose the aging structures, Les Halles underwent significant redevelopment. This transformation aimed to preserve the historical essence of Les Halles while integrating contemporary architectural elements and amenities.

The Canopy (Le Grand Palais de Les Halles):

Le Grand Palais de Les Halles is the centerpiece of the modern redevelopment. Designed by Jacques Anziutti and Patrick Berger, The Canopy embodies a blend of historical reverence and modern innovation.

Key Features of The Canopy:

- Glass and Metal Structure: The canopy's extensive use of glass and metal pays homage to the original industrial aesthetic of the 19th-century Les Halles while introducing a sleek, contemporary look.

- Spacious Interior: The design ensures vast, open spaces that facilitate easy navigation for shoppers and visitors, enhancing the overall user experience.

- Sustainability: Incorporating energy-efficient systems and sustainable materials, The Canopy aligns with modern environmental standards, reducing its ecological footprint.

- Integration with Urban Infrastructure: The canopy seamlessly connects with Paris's existing transportation networks, including proximity to major metro lines and bus routes, ensuring accessibility and convenience.

Annex

The Construction and Organization of Les Halles Centrales (1857 - 1874)

The construction of Les Halles Centrales began with a royal ordinance on January 17, 1847. The first stone was laid on September 15, 1851, marking the initial phase of development. However, the original pavilion, constructed from stone, was deemed too heavy and massive, leading to its demolition. Architects Baltard and Callet then revised the design, opting for a more modern approach that utilized iron and cast iron. The first of these pavilions was inaugurated in 1857.

Phased Pavilion Installation Timeline

- West Group: Pavilions 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12 were completed between 1857 and 1858.

- East Group: Pavilions 3, 4, 5, and 6 were completed between 1860 and 1874.

Each pavilion served distinct market functions:

- Pavilion 11 (1857): Fruits, vegetables, and poultry

- Pavilion 9 (1857): Fish

- Pavilion 10 (1858): Butter, eggs, and cheese

- Pavilions 3, 4, 5, and 6 (1860–1874): Butchery, poultry, and game

Collectively, the 10 pavilions covered a total surface area of 25,272 square meters.

Additional Infrastructure

- Covered Pathways: 9,045 square meters

- Total Area of Les Halles: 34,317 square meters

- Subterranean Storage: Doubled the usable area for storing equipment, goods, and empty containers

- Surrounding Streets (Baltard, Rambuteau, Berger, and Pierre-Lescot): Expanded available area to 5 hectares

Construction Costs

| Item | Cost (Francs) |

|---|---|

| Construction of 10 pavilions | 14,000,000 |

| Electrical and water installations | 1,000,000 |

| Land acquisition (15,000 m²) | 15,000,000 |

| Expropriations | 35,000,000 |

| Total | 65,000,000 |

Revenue (1900)

| Source of Revenue | Amount (Francs) |

|---|---|

| Wholesale sales (shelter fees) | 2,781,084 |

| Retail sales (occupation fees) | 598,725 |

| Office and storage rentals | 56,573 |

| Public weighing fees | 252,486 |

| Cleaning services | 10,603 |

| Street market fees | 520,307 |

| Parking fees (net of abatements) | 908,622 |

| Total Revenue | 5,128,403 |

Lighting in Paris and Les Halles

Evolution of Lighting in Paris

Before 1318, Paris had no public lighting, leaving its streets in complete darkness during the night. From 1318 to 1558, the city's public lighting consisted of a single candle, a modest attempt to brighten the streets.

In 1550, the Parliament ordered the placement of falots (pitch pots) at every street corner, illuminating the city from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m., a measure soon improved upon by replacing the pitch pots with lanterns containing candles.

By 1667, during the reign of Louis XIV, 5,000 candle-lit lanterns illuminated the public streets of Paris, with maintenance shouldered by the bourgeois of each district. This figure later grew to 6,500 lanterns.

Over time, oil lamps replaced candles as the preferred method of public lighting, marking a significant technological step forward. The first experiment with gas lighting occurred in 1817 at the Passage des Panoramas, a bustling and popular location.

By 1863, over 1,300 gas lamps lit up Les Halles Centrales, a hub of activity in Paris. By 1882, the cost of lighting Les Halles had reached 200,000 francs, reflecting both the growing scale and expense of public illumination.

Breakdown of Gas Lamps at Les Halles (1882)

| Location | Number of Gas Lamps |

|---|---|

| Covered pathways | 808 |

| Basement | 413 |

| Outdoor market space | 208 |

| Total | 1,373 |

In 1878, the first trial of electric lighting took place during the Exposition Universelle, showcasing the potential of this revolutionary technology. Following its success, electric lighting rapidly supplanted gas lighting at Les Halles, marking a significant transformation in urban illumination.

On December 1, 1889 the municipal electricity plant for Les Halles Centrales was inaugurated.

Breakdown of Electric Lighting at Les Halles (October 24, 1902)

| Location | Number of Lamps |

|---|---|

| Ground floor (arc lamps) | 265 |

| Basement (arc lamps) | 396 |

| Outdoor market space | 48 arc lamps, 176 incandescent |

| Total | 886 lighting points |

Forum des Halles Phased Development Plan (1970s)

Phase I: Les Halles Development

- Construction of a 300-room hotel adjacent to an exhibition center near La Bourse, positioned at the core of the business district.

- The hotel and exhibition center open to a vast park, similar to the Forum’s outdoor meeting areas.

- Below the park, facilities include residential parking, sports amenities, and the Paris Telephone and Telegraph (PTT).

Phase II: Transportation and Cultural Spaces

- Introduction of a multi-level entrance to the metro and RER systems.

- Development of exhibition spaces leading to a Museum of France, showcasing the country’s industries, customs, and arts across all departments.

Phase III: Educational Facilities

- Establishment of Les Grandes Écoles, serving as academic institutions affiliated with the Pompidou Center.

Sources & References

Destroying the Mystique of Paris: How the Destruction of Les Halles Served as a Symbol for Gaullist Power and Modernization in 1960s and 1970s Paris. Scott A. Kasten, Georgia State University. 2013

Le général de Gaulle, acteur de la rénovation du quartier des Halles, à Paris. Nicole Even. Actes des congrès nationaux des sociétés historiques et scientifiques 2012

Halles Centrales de Paris. Autrefois et aujourd'hui. M. Jules Vigneau. 1903

Les Halles. Paris France. Richard G. Carrell. 1979

Les Halles, lieu d'une seule jeunesse. Un monde commun de styles différenciés. Catherine Hass, Marianne Hérard. Les Annales de la recherche urbaine. 2008

Les Halles, Paris sous sol. Flux et regards sous contrôle. Anne Jarrigeon. Ethnologie française, XLII. 2012

Les Halles: A series of unfortunate events. Rachael McCall. 2011

Les Halles Centrales de Paris Construites sous le Règne de Napoléon III par V. Baltard & F. Callet. A. Morel et Cie, Libraires-Éditeurs. 1862

__

Last updated: 11 December 2024