Pleasure Gardens, Georgian Gardens: The Rise and Legacy of Urban Leisure Spaces Gardens

In the late 17th and 18th centuries, pleasure gardens emerged as vital components of Georgian society, providing urban dwellers with spaces for leisure, entertainment, and social interaction.

Gardens such as Vauxhall, Ranelagh, Marylebone, and Sydney Gardens became cultural hubs where artfully designed natural settings and diverse entertainments converged, reflecting the era's evolving social and cultural dynamics.

The Emergence of Pleasure Gardens

Origins in England's Restoration Period

The concept of the pleasure garden as a public entertainment venue originated in England during the Restoration period.

The Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 marked a pivotal moment in London's cultural history. After two decades of Puritan austerity during the Interregnum, the reopening of theatres and the emergence of pleasure gardens signified a revival of public entertainment and social interaction. These pleasure gardens provided an idealized escape from the city's squalor, offering a blend of nature, art, and leisure that appealed to people across social strata.

The Genesis of Pleasure Gardens

Spring Gardens at St. James's Park

- Origins: Established during the reign of Elizabeth I, the Spring Garden in St. James's Park was among the earliest public gardens, named after a natural spring on the site.

- Features: By the early 17th century, it boasted a bathing pond, fountains, gravel paths, fruit trees, and even exotic animals. It served as a promenade for the upper classes, allowing them to mingle with royalty and aristocracy.

- Cultural Significance: Diarist John Evelyn described it in 1653 as a "Paradise," highlighting its appeal even during the restrictive years of the Commonwealth.

The Old and New Spring Gardens at Vauxhall

- Old Spring Gardens: Little is known about the older garden, but it was referenced by Samuel Pepys in 1662, indicating its existence prior to the New Spring Gardens.

- New Spring Gardens: Opened around 1661 in Vauxhall, it quickly became a popular retreat. Spanning over 11 acres, it featured wooded areas, covered walks, arbours for privacy, and huts serving food and drink.

- Accessibility: Located on the south bank of the Thames, visitors often reached it by a pleasant 30-minute boat ride, adding to the experience.

- Activities and Reputation:

- Entertainment: Visitors enjoyed acrobatic performances, music, and the natural choruses of songbirds, particularly nightingales.

- Social Dynamics: The gardens were known for their relaxed atmosphere, where people could promenade safely, engage in merriment, and even indulge in amorous encounters.

Cuper's Gardens: A Blend of Art and Leisure

- Establishment: Created by Abraham Boydell Cuper, gardener to the Earl of Arundel, on land leased from the Howard family.

- Unique Features:

- Antiquities: Incorporated remnants of the Earl's collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, salvaged after Arundel House was demolished in 1678. These artifacts lined the central walkway, adding cultural depth.

- Entertainment: Offered winding paths through trees, music performances, a bowling green, and a rectangular pond.

- Reputation: Gained a nickname "Cupid's Gardens" due to its association with romantic liaisons.

- Evolution and Decline:

- Improvements: Under Ephraim Evans in 1738, the gardens saw enhancements like an orchestra pavilion and an organ.

- Challenges: Became notorious for pickpockets, leading to the loss of its license in 1753. It operated as an unlicensed tea garden until its closure in 1760.

Other Noteworthy Pleasure Venues

Mother Huff's Tea Garden

- Location: Situated off Spaniard's Road in Hampstead.

- Timeline: Opened in 1678 and thrived for 50 years.

- Offerings: Despite its name, it was licensed to sell alcohol, attracting visitors seeking both tea and stronger libations.

The Folly: A Floating Musical Summer-House

- Description: A unique entertainment venue built on a floating platform on the Thames, downstream of Waterloo Bridge.

- Features: Rectangular structure with five turrets, accessible only by boat, adding exclusivity and allure.

- Cultural Note: Mentioned briefly by Samuel Pepys in 1668 as "the Folly." By 1700, it had a dubious reputation, associated with "amorous intrigues" and later became a gambling den.

Georgian Pleasure Gardens: The Rise and Legacy of Urban Leisure Spaces

Design and Accessibility

Designed not merely for relaxation but for a variety of entertainments, Georgian pleasure gardens catered to the burgeoning middle class and the aristocracy alike. They provided meticulously maintained natural settings where visitors could escape urban life's grime and indulge in the aesthetic and recreational offerings of the time.

Entertainment and Cultural Significance

Integration of the Arts

Pleasure gardens were closely associated with the arts, particularly music and theater. They hosted concerts, balls, plays, firework displays, and even hot air balloon ascents, making them the Georgian equivalent of modern theme parks. This integration of diverse forms of entertainment attracted a broad audience, fostering a vibrant cultural scene.

Musical Innovations

Music was integral to the appeal of pleasure gardens. Composers like George Frideric Handel debuted new pieces at venues like Vauxhall Gardens. Notably, Handel’s "Music for the Royal Fireworks" was first rehearsed at Vauxhall in 1749, drawing immense crowds and causing traffic jams as thousands flocked to hear it. These performances not only entertained but also showcased the era's musical innovations.

Artistic Collaborations

Artists like William Hogarth collaborated with garden proprietors to include paintings within each supper box, enhancing the aesthetic experience and contributing to the gardens' triumph. This blend of nature, art, and entertainment created an immersive environment that was both sophisticated and accessible.

Social Mixing and Masquerades

Facilitating Social Interaction

One of the most intriguing aspects of pleasure gardens was the social mixing they facilitated. For an admission fee, individuals from different social strata could mingle, breaking down rigid class barriers and promoting a more inclusive social atmosphere.

Masquerade Nights

Masquerade nights added an element of intrigue and anonymity, allowing visitors to interact outside the strict social norms of the time. This aspect provided an exciting frisson in an era governed by strict etiquette, enabling a temporary suspension of societal constraints and fostering social fluidity.

Vauxhall Gardens: The Epitome of Regency London's Social and Cultural Life

In the heart of Georgian London, Vauxhall Gardens emerged as a pioneering force in mass entertainment and social diversity. From its humble beginnings in the mid-17th century to its closure in 1859, Vauxhall Gardens played a pivotal role in shaping the city's cultural landscape. Offering a unique blend of natural beauty, art, music, and diverse attractions, the gardens became a microcosm of London's evolving urban society.

A Hub of Social Diversity and Entertainment

Vauxhall Gardens were more than just a place of leisure; they were a social melting pot where nobility mingled with merchants, artists, and even less reputable members of society.

The gardens provided an environment where class barriers were temporarily suspended, allowing for rich interactions and experiences. This unique social dynamic made Vauxhall an ideal backdrop for literary works of the period, such as Fanny Burney's Evelina and Tobias Smollett's The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, and continues to inspire contemporary historical fiction.

Historical Overview

Early Beginnings: The New Spring Garden (1661-1728)

Originally established as the New Spring Garden in 1661, Vauxhall was a rural tavern and leisure spot adorned with commercial hardwoods and perfumed flowers. Located on the south bank of the Thames, visitors often reached it by a pleasant 30-minute boat ride, adding to the allure. The gardens featured wooden arbours, makeshift retreats, and promenading areas, making it a popular destination for relaxation and social interaction.

The Tyers Era: Transformation into a Cultural Hub (1729-1792)

In 1729, Jonathan Tyers acquired Vauxhall Gardens and redefined them as a refined pleasure garden dedicated to civilized entertainment. Under his visionary management, the gardens reopened in 1732 with a grand Ridotto al Fresco, marking the beginning of their golden era.

Cultural Collaborations and Innovations

- Artistic Enhancements: Collaborations with renowned artists like William Hogarth and Francis Hayman enriched the visual experience. Sculptures by Louis François Roubiliac added to the gardens' grandeur.

- Musical Contributions: Music was integral to the Vauxhall experience. Composers like George Frideric Handel had their works performed regularly, elevating the gardens' cultural significance.

- Architectural Developments: Tyers introduced structures like the Orchestra, one of London's first dedicated music performance buildings, and innovative use of lighting with over 20,000 oil lamps by 1822.

Mass Entertainment and Commercialization (1793-1859)

Following Tyers' death, Vauxhall Gardens embraced the rise of mass entertainment.

Expansion and Diversification

- Spectacular Events: Hosted balloon flights, fireworks displays, masquerades, and circus performances, attracting thousands each season.

- Mechanical Attractions: Introduced attractions like the Cascade and featured performances by acrobats and tightrope walkers, notably Madame Saqui from 1816 to 1820.

- Culinary Offerings: Dining in elegantly decorated supper boxes with menus featuring cold meats, salads, pastries, and the famous arrack punch became a social custom.

Challenges and Closure

Despite efforts to modernize, Vauxhall faced financial challenges due to competition and changing tastes. The advent of railways and new entertainment forms led to a decline in attendance. The gardens closed permanently in 1859, marking the end of an iconic chapter in London's social history.

Accessibility and Admission

One of Vauxhall's most appealing aspects was its accessibility.

Open to anyone who could afford the admission fee, the gardens welcomed a broad spectrum of society. The entrance fee evolved over time, starting at one shilling and increasing to three shillings and sixpence by the early 19th century. Season tickets offered regular patrons a cost-effective option. The opening of Westminster Bridge in 1750 and later Vauxhall Bridge in 1816 made the gardens more accessible by road, enhancing their appeal.

Architectural and Aesthetic Appeal

Vauxhall Gardens were renowned for their enchanting atmosphere, created through meticulous landscaping and innovative lighting. Winding pathways, illuminated groves, and an array of pavilions, temples, and statues captivated visitors. The extensive use of oil lamps produced a mesmerizing spectacle, setting a standard for public illumination in urban spaces.

Cultural Significance

Shaping Public Entertainment

Vauxhall Gardens played a pivotal role in shaping public entertainment and social life in London. As one of the first venues to offer mass entertainment accessible to a broad audience, it fostered a sense of community and provided a platform for artistic and musical innovation.

Influence on Modern Amusement Parks

The legacy of Vauxhall Gardens is evident in the design and concept of contemporary amusement parks. Its harmonious blend of natural beauty with diverse attractions set the standard for future entertainment venues, influencing the integration of art, music, and recreation in urban leisure spaces.

Vauxhall Gardens in Literature and Modern Media

The gardens have been immortalized in numerous literary works, reflecting their significance in Regency society. Authors like William Makepeace Thackeray featured Vauxhall in novels such as Vanity Fair, using the setting to explore themes of social mobility and morality.

Today, the legacy of Vauxhall Gardens is commemorated through remnants like the Royal Vauxhall Tavern and historical artifacts housed in museums. The site now features Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, a modern park that hosts community events and cultural activities, continuing the tradition of urban leisure.

Ranelagh Gardens: A Tale of Two Cities' Pleasure Landscapes

In the vibrant tapestry of 18th-century London, a new kind of social venue emerged that would redefine urban life and culture. The Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens, nestled near the banks of the Thames by Chelsea Hospital, were more than mere amusement parks; they were the embodiment of Enlightenment ideals, where art, society, and entertainment converged.

Tracing the Roots of Pleasure in Dublin and London

The phenomenon of pleasure gardens blossomed during the 18th century, offering urban dwellers an escape from the hustle and bustle of city life. London's Ranelagh Gardens set a benchmark with its grandeur and sophistication, inspiring Dublin to create its own version tailored to the Irish context.

Ranelagh in Dublin: From Private Estate to Public Escape

The Birth of Dublin's Ranelagh Gardens

Located on the Willsbrook Estate south of Dublin, the grounds that would become Dublin's Ranelagh were steeped in history. Originally part of the medieval farm of St. Sepulchre, the land transitioned into the hands of Rt. Rev. Dr. William Barnard, Bishop of Derry, in the mid-18th century. Under Barnard, the estate gained a reputation for elite hospitality.

After Barnard's death in 1768, William Castel Hollister, a harpsichord maker, transformed the estate into Dublin's Ranelagh Gardens. Drawing inspiration from London's celebrated pleasure grounds, Hollister sought to replicate the allure while tailoring it to Dublin's social landscape.

Adapting the Pleasure Garden Concept

Opening 35 years after its London counterpart, Dublin's Ranelagh offered music, promenades, and theatrical entertainment. Though smaller in scale, it catered to a diverse audience, becoming a social hub that reflected Dublin's evolving urban identity.

London's Ranelagh: A Model of Grandeur

A Cultural Oasis in a Growing Metropolis

As London burgeoned into a global city, spaces like Ranelagh became essential retreats for those seeking respite from the crowded streets. Designed to appeal to both the aristocracy and the affluent middle class, Ranelagh offered an environment where luxury and cultural refinement coexisted.

Admission fees played a crucial role in shaping the garden's exclusivity. While venues like Vauxhall Gardens were accessible to the masses, Ranelagh's prices—ranging from two shillings on regular days to forty-two shillings for grand masquerades—ensured a distinguished clientele. Advertisements touted the presence of "nobility and gentry," cultivating an image of prestige.

Yet, Ranelagh wasn't entirely insular. Occasionally, the gardens welcomed groups like the children from the Foundling Hospital, reflecting a nuanced social mix. Such inclusivity hinted at the complex social dynamics of the time, where charity and exclusivity intertwined.

Architectural Splendor Meets Artistic Flair

The physical space of Ranelagh was a marvel in itself, meticulously crafted to immerse visitors in contemporary cultural trends.

The Enchanting Gardens

Meandering alleys invited leisurely strolls, while a serene canal featured a Chinese pavilion—a nod to the era's fascination with the exotic. At night, the gardens transformed under the glow of countless lanterns, creating an ethereal atmosphere that blurred the lines between reality and fantasy.

The Majestic Rotunda

The crown jewel of Ranelagh was undoubtedly its immense rotunda. Spanning 150 feet in diameter, this architectural wonder boasted fifty-two elegantly decorated boxes and a ceiling adorned with celestial motifs. Initially serving as the orchestra's domain, the rotunda evolved to include fireplaces, catering to the patrons' growing desire for comfort without sacrificing grandeur.

A Stage for Spectacle and Entertainment

Ranelagh was synonymous with entertainment that dazzled the senses and stimulated the mind, aligning with the Enlightenment's spirit of exploration and discovery.

Musical Delights

Music resonated at the heart of Ranelagh's appeal. Twice weekly, garden concerts filled the air with harmonious melodies. A landmark moment came in 1764 when an eight-year-old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart graced the rotunda, enchanting audiences and solidifying the venue's reputation as a cultural hub.

Masquerades of Mystery

Drawing inspiration from Italian traditions, Ranelagh's masquerades were events of opulence and intrigue. Guests adorned themselves in elaborate costumes, embracing a temporary suspension of societal norms. These evenings were more than mere parties; they were immersive experiences that celebrated exoticism and the era's cosmopolitan ethos.

Fireworks and Spectacles

The gardens didn't shy away from grand displays. In 1792, the "Etna" volcanic explosion show captivated audiences by blending scientific curiosity with theatrical flair. Such events catered to the public's appetite for wonder, embodying the Enlightenment's encouragement of scientific and artistic exploration.

Dining at Ranelagh Gardens

In the 18th and 19th centuries, long before the advent of modern restaurants, Londoners seeking a novel dining experience turned to pleasure gardens like Ranelagh. These venues introduced the concept of dining out for enjoyment rather than necessity, marking a significant cultural shift in urban leisure activities.

A Novel Dining Experience Under the Stars

Pleasure gardens were outdoor venues where visitors could spend hours indulging in music, art, dancing, and socializing. Amidst these activities, the opportunity to dine publicly was a unique attraction.

Ranelagh provided designated areas within its grand rotunda where guests could order food and drink, such as roast chicken, wafer-thin slices of ham or beef, bread and butter, salads, olives, confectionery, and seasonal fruits. Similarly, Vauxhall's open-air supper boxes offered an elegant setting for dining, enhancing the gardens' atmosphere of sophistication and social interaction.

This setting marked a departure from traditional dining norms. For the first time, the wealthy and emerging middle classes were eating in public view, transforming dining into a social spectacle. Patrons often dressed in their finest attire, turning meals into displays of elegance and status.

The High Cost of Dining Out

Dining at Ranelagh came at a premium. While admission fees ensured an exclusive clientele, the cost of food inside was steep compared to other dining options of the time. A single slice of ham or beef could cost as much as the entrance fee, making dining a status symbol.

Despite the modest portions and simple menus, the act of dining in public view transformed it into a social spectacle, emphasizing one's social standing and visibility.

Dining as Part of the Social Experience

Despite the underwhelming culinary offerings, dining at Ranelagh was less about the food and more about the social ritual. It provided an opportunity to:

- Engage in Conversation: Supper boxes allowed for intimate gatherings where guests could converse freely while enjoying the evening's entertainments.

- Observe and Be Observed: Eating in public view turned dining into a performance, enhancing one's social standing and visibility.

- Extend the Evening: Meals provided a break between activities like dancing or viewing art exhibits, allowing patrons to prolong their enjoyment of the gardens.

In Thomas Rowlandson's depiction of Vauxhall, notable figures such as Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, Oliver Goldsmith, and Hester Thrale are seen dining together, highlighting the gardens' role as a gathering place for London's intellectual and social elite.

Social Alchemy: Mixing of Classes and Cultures

While Ranelagh cultivated an image of exclusivity, it also served as a melting pot where different social strata could intersect, albeit within certain confines.

The Art of Being Seen

For London's elite, Ranelagh was as much about visibility as it was about enjoyment. Strolling through the illuminated gardens, patrons engaged in the unspoken dance of social observation—assessing attire, manners, and potential alliances.

Bridging Social Divides

Though the gardens primarily attracted the upper echelons, the presence of diverse groups hinted at subtle shifts in societal structures. Interactions across classes, while limited, signaled the early stirrings of a more interconnected urban society.

Echoes of Praise and Critique

Contemporary reactions to Ranelagh were as varied as its attractions, offering insights into its multifaceted impact.

A Skeptic's View

Contrastingly, Lydia's uncle, Matthew Bramble, offers a sardonic critique:

"An eternal round of insipid pleasures and shallow pursuits. Tea-drinking in circles and walking in perpetual circuits—what folly!"

Bramble's disdain highlights a perception of Ranelagh as superficial—a veneer of sophistication masking a lack of substantive engagement.

An "Enchanted Palace"

In Tobias Smollett’s 1771 novel Humphry Clinker, the character Lydia effusively describes Ranelagh:

"O, what a paradise! Illuminated by a thousand golden lamps, adorned with the finest paintings, and filled with the most elegant company."

Her romanticized portrayal captures the awe that Ranelagh inspired—a place where reality seemed to give way to enchantment.

A Legacy Etched in Urban Fabric

Ranelagh Pleasure Gardens were more than a venue; they were a phenomenon that encapsulated the complexities of 18th-century London. By offering a space where art, nature, and society converged, Ranelagh became a microcosm of broader cultural shifts.

Its influence extended beyond entertainment. The gardens hosted celebrations for significant events, such as the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1749 and the Prince of Wales’ birthday in 1759, intertwining national identity with social leisure.

Legacy and Influence

Shaping Urban Leisure and Recreation

Ranelagh Gardens, alongside venues like Vauxhall and Marylebone Gardens, played a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of urban leisure and social interaction in London.

These pleasure gardens pioneered the integration of natural beauty with cultural and social entertainments, setting standards for public recreational spaces that would influence urban planning and the development of modern amusement parks.

Enduring Impact on Urban Culture

The legacy of Ranelagh Gardens is evident in the continued emphasis on creating multifaceted public spaces that cater to both aesthetic enjoyment and social engagement.

Modern parks and entertainment venues often mirror the harmonious blend of art, nature, and social activities that Ranelagh exemplified, underscoring its lasting influence on urban cultural life.

Transition to Modern Recreational Spaces

With the changing fashions and mindsets of the mid-19th century, the model of pleasure gardens evolved into more urbanized recreational spaces like the galleries of the Palais Royal. However, the foundational concepts of communal leisure and entertainment established by the Georgian pleasure gardens remain integral to the design of public leisure spaces today.

Legacy and Influence of Pleasure Gardens

Despite their decline in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pleasure gardens like Ranelagh and Vauxhall left a lasting legacy on urban recreational spaces.

They pioneered the integration of natural beauty with cultural and social entertainments, laying the groundwork for modern public parks and amusement parks.

Modern public parks often feature bandstands, open-air theaters, and spaces for community events, mirroring the multifunctional nature of pleasure gardens. The harmonious blend of art, music, and recreation in a natural setting continues to inspire contemporary urban planning and the creation of multifunctional public spaces.

_

Sources and Images

Fig. 2 - Philibert-Louis Debucourt, a distinguished printmaker and social satirist, engaged in artistic dialogue with his British contemporaries during periods of significant political upheaval. As Paris braced for revolutionary turmoil, Debucourt depicted the fashionable elite leisurely interacting in the gardens of the Palais-Royal. This portrayal drew inspiration from Thomas Rowlandson's color aquatint, which captured a contented assembly in London's verdant Vauxhall Gardens.

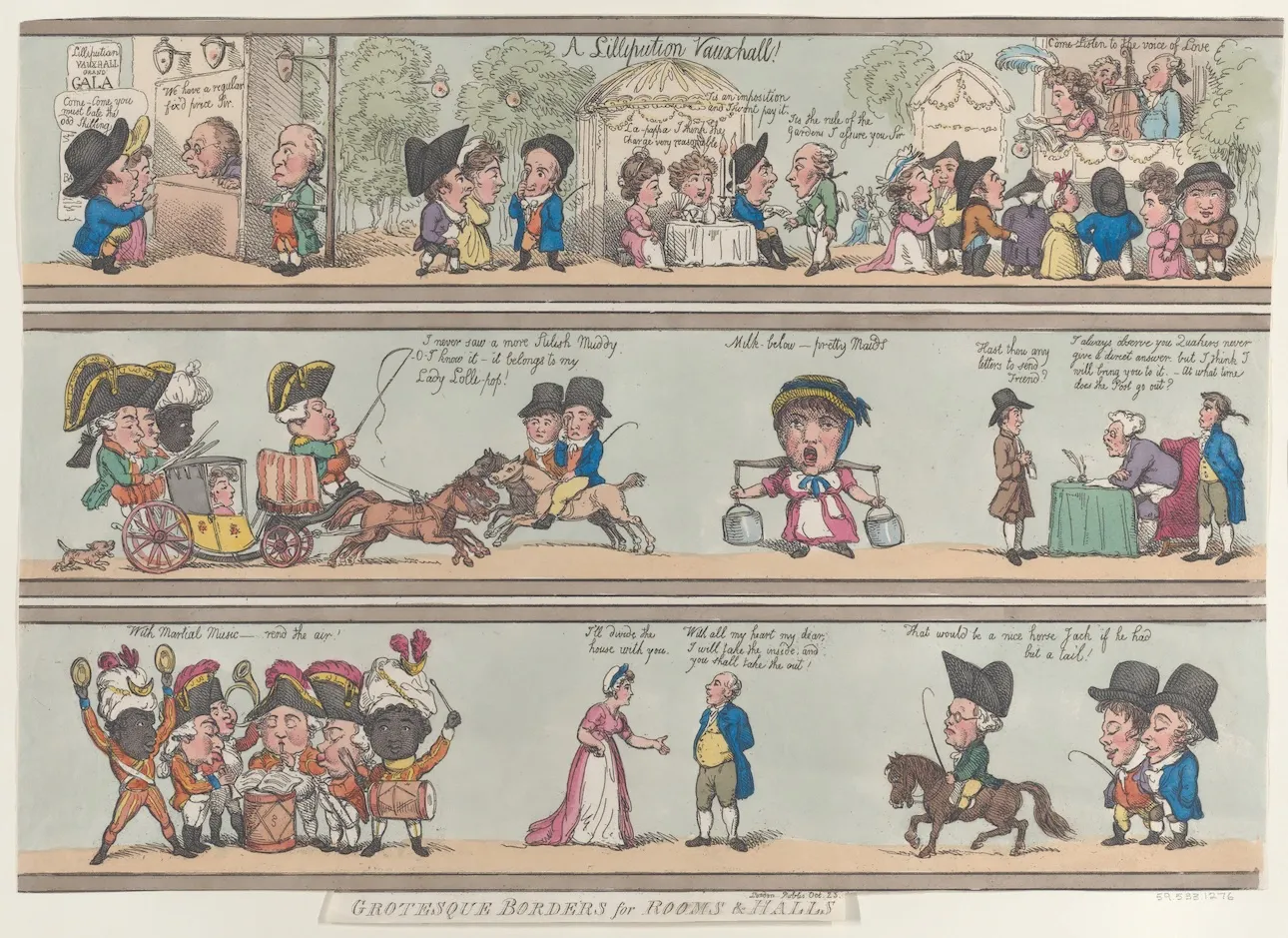

Fig. 3 - A Lilliputian Vauxhall is a hand-colored etching by British artist Thomas Rowlandson, based on designs by George Murgatroyd Woodward. Published by Rudolph Ackermann, the piece is titled "A Lilliputian Vauxhall, Grotesque Borders for Rooms & Halls." It features three horizontally arranged strips depicting various scenes. It can be interpreted as a depiction of a miniature or trivialized version of the social and entertainment scenes characteristic of Vauxhall Gardens, possibly serving as a satirical commentary on the societal norms and behaviors of the time.

Fig. 5 - Sir Thomas Robinson, 1st Baronet (circa 1703–1777), was an English architect, collector, and politician. He served as the Governor of Barbados from 1742 to 1747 and was a Member of Parliament for Morpeth from 1727 to 1734. Known for his tall stature, he was colloquially referred to as "Long Sir Thomas."

Robinson was instrumental in the development of Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea, London. In 1741, he led a consortium that acquired the property, transforming it into a prominent public pleasure garden that opened in 1742. Under his management, Ranelagh Gardens became a fashionable venue, featuring a notable rotunda that hosted concerts and social events, thereby playing a significant role in London's 18th-century social scene.

His multifaceted career and contributions to London's cultural life made him a subject of interest among contemporaries, including satirists like William Austin, who depicted him in caricatures that humorously critiqued societal norms of the time.

This particular design targets Sir Thomas Robinson, by this time, in his seventies, humorously depicted in an outdated suit, escorting his elderly mistress to the Pantheon, London’s latest fashionable hotspot, which also hosted masquerades. The print cleverly suggests that their advanced age and deteriorating vision have rendered their real faces as effective as masks.

__

Last updated: 8th December 2024